History of Shenandoah Mountain

|

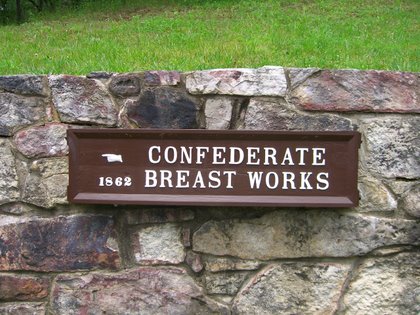

Shenandoah Mountain has a fascinating history. We can only imagine what the forest was like when settlers began to move into the Shenandoah Valley. We do know that Shenandoah Mountain played a critical role in the Civil War. Fort Edward Johnson, located on the crest of Shenandoah Mountain just north of Rt. 250 and now known as Confederate Breastworks, was instrumental in defending the town of Staunton during the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862. Frank Jones, a major in Stonewall Jackson's Army, gives a glimpse of what Shenandoah Mountain was like then in an entry in his diary, "I have been struck with the wild mountain scenery. The Shenandoah Mountain Pass is grand indeed, you ascend to the top of the mountain and from there you can see as far as the eye can reach. Mtn. after Mtn. in every variety of shape and grandeur... Every now and then you will find a fresh and sparkling stream gushing out of the mtn. side and running away into the larger streams in the Valley."

The forest that had existed on Shenandoah Mountain was reduced to a wasteland in the latter half of the nineteenth century due to promiscuous expansion and exploitation. Farming, mining, and logging all took their toll. During the same period turkey, bear, deer, and many other species were driven nearly to extinction in western Virginia due to overhunting and poor land management practices. The damage to the watershed from all the mining, logging, and subsequent burning led to clogged streams and flooding. When the forests were gone, repeated fires degraded the soils and stunted new growth. Even the forests today are poorer because of the soil damage and loss.

In response to all the devastation of the mountain forests, the U.S. Congress passed the Weeks Act in 1911, giving the federal government authority to purchase the mostly wasted land to protect watersheds. The Shenandoah Purchase Unit, which includes the Shenandoah Mountain area, was among the first land to be purchased.. The newly purchased forest land became Shenandoah National Forest in 1917. The name was changed to George Washington National Forest in 1932 to avoid confusion with Shenandoah National Park to the east of the Valley. I

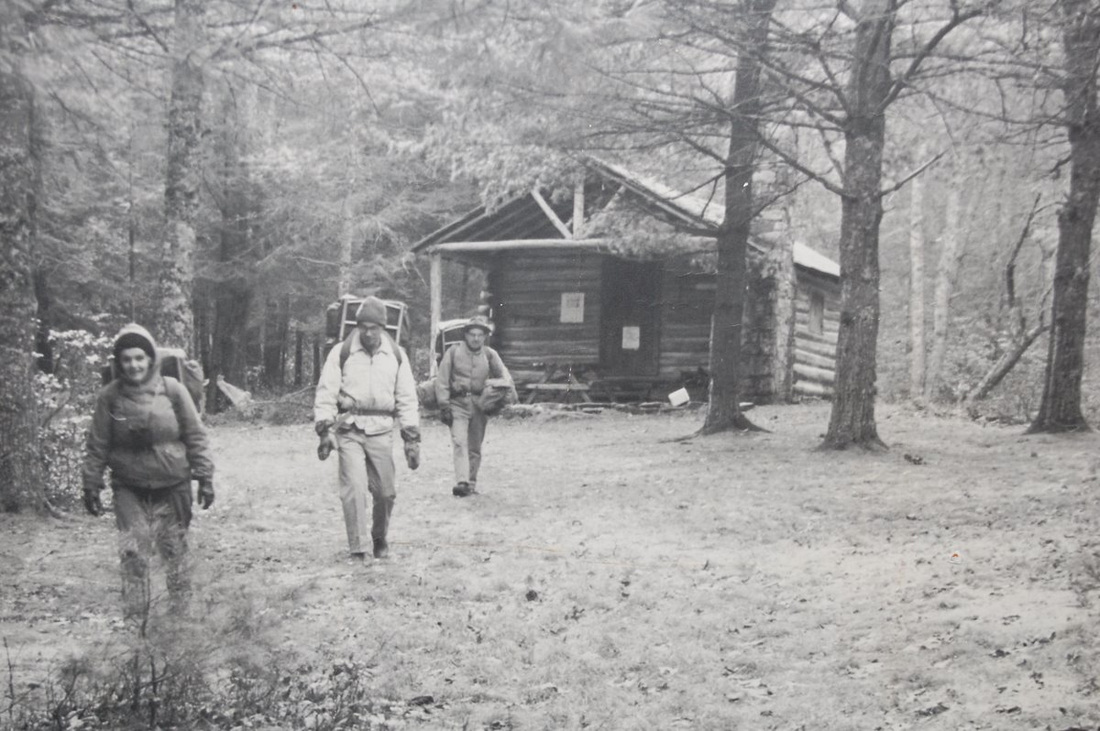

Initially, local mountain people did not take well to the federal government acquiring the land; many set fires on the land purchased by the government. Up through the 1920s, forestry officials estimated up to 94 percent of the fires were caused by man. In response to the natural and man-caused fires, a fire warden system was developed. A warden would be in charge of an area and would have a crew of local firefighters. One of these was organized from the students of Bridgewater College. Fire wardens used remote lookout towers and telephone lines for spotting fires and calling for help. Several of these fire towers were located on Shenandoah Mountain: High Knob (still standing and renovated in 2001-03), Bother Knob, Flagpole Knob, Reddish Knob, and Hardscrabble Knob The fire warden system began to fade out between the 1940s through 1960s with the advent of the Smokey Bear campaign. Then aerial flights were used to detect fires, eliminating the need for men in towers. By the 1980s there were enough people living close to the forest to see and report fires, making even aerial flights unnecessary. See History of High Knob Fire Tower During the period between 1910 and 1925, chestnut blight moved through the area, killing the most productive and dominant species in the forest. The Great Depression caused timber prices to plummet. President Roosevelt, however, poured New Deal money into land acquisitions for the National Forests. He also started the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in 1933, providing 9,200 unemployed young men in Virginia with meaningful work and modest pay sufficient to support their families. The first CCC camp in the nation was located at Camp Roosevelt in the George Washington National Forest. Fourteen camps were located in the GW, with at least one located along the North River in the Shenandoah Mountain area. The workers built roads, telephone lines, trails, and campgrounds. Shenandoah Mountain was and continues to be the beneficiary of work done by the CCC in its nine years of existence. Even on remote trails in the backcountry, one can see CCC rockwork that still holds the trails in place today.

|

As the forests and streams began to recover from past abuse, the Forest Service began to sell timber and develop the area for recreational and scenic values. The State of Virginia began to manage wildlife as it returned to the recovering landscape. The two agencies worked together to develop small herds of deer and stock streams with trout. They even tried to reintroduce elk in 1917 and 1935, but efforts were unsuccessful because too much of the species’ undisturbed habitat was already gone. In 1960, the Multiple Use act was passed. In 1964 the Wilderness Act was passed and was followed by the Eastern Wilderness Areas Act in 1975. Although the U.S. Congress has designated Wilderness areas in Virginia four times, only one of these, Ramseys Draft Wilderness (6,518 acres), is located in the proposed Shenandoah Mountain National Scenic Area. This is despite several initiatives by citizens groups over past decades to add more of Shenandoah Mountain to the Wilderness system.

In addition to destruction caused by man, Shenandoah Mountain has experienced several significant natural events. The flood of 1949 scoured the Little River and caused major flooding downstream along the North River and in the town of Bridgewater. This flood provided the impetus for the construction of the series of flood-control dams in the headwaters of the North River drainage. In 1985, Shenandoah Mountain again experienced a major flood with over 20 inches of rain in a few days. In the mid-1980s the invasive gypsy moth made its way to the area, defoliating and killing trees along the way, particularly on ridgetops. The gypsy moth population crashed suddenly in 1996 due to the fungus (Entomophaga maimaiga). Following World War II, society became more mobile and prosperous. Recreational use of the forest increased by leaps and bounds and continues today.

Source: Satterthwaite, Jean L. George Washington National Forest: A History. USFS, 1993 and USFS web site. |