Exploring Shenandoah Mountain's History

High Knob Fire Tower

Tyler Gingrich and Caroline Whitlow

James Madison University

See Hike to High Knob Fire Tower (with Map)

James Madison University

See Hike to High Knob Fire Tower (with Map)

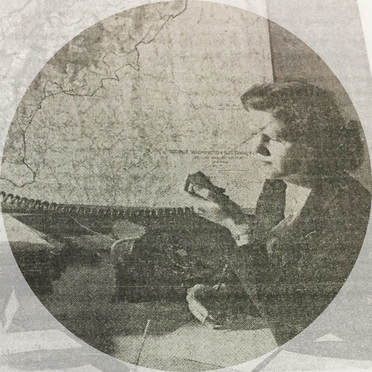

Ethel Miller, who worked in Bridgewater as a radio dispatcher to the fire towers and later became Gerald Fawley’s wife.

Ethel Miller, who worked in Bridgewater as a radio dispatcher to the fire towers and later became Gerald Fawley’s wife.

Gerald Fawley, Fire Watch

As nighttime closes in and the autumn air cools, not even a silhouette of the tree line remains visible along the darkening mountainside. Quietness trumps over the occasional sound of an evening bird or small creatures trampling on fallen brown leaves. The watchman retreats to his cabin and huddles around a Kerosene lamp, as occasional storms provide the only source of natural luminescence with lightning that could jolt a man's nerves straight through. This is the solitude of the vigilant life of a fire tower watchman like Gerald Fawley, who spent his days over 4,000 feet in the air on Shenandoah Mountain.

Gerald Fawley, Class of 1935, had just graduated from Broadway High School in Rockingham County when he landed a position with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). As a Local Enlisted Man (LEM), Fawley completed tasks from working as a typist to delivering lunches for work crews all over the Shenandoah Valley. After the CCC camp closed in 1937, Fawley had no trouble finding a new position. He began working with the Forest Service, a federal agency underneath the Department of Agriculture. Henceforth, Fawley’s work centered around the natural development and functional use of the newly renamed George Washington National Forest, known as Shenandoah National Forest from its founding in 1917 to 1932.

Lacking training or experience with explosives, the college-aged man hauled thousands of pounds of dynamite for the men he called "dynamite monkeys" who oversaw CCC road projects. When the fire season rolled around, the Forest Service posted Fawley at a steel lookout tower on the crest of Shenandoah Mountain at Bother Knob. From his metal perch, Fawley watched for potential forest fires and phoned a dispatch station in Bridgewater if smoke or flames arose. He found entertainment in the wildlife of his workplace— turkeys, rabbits, foxes, and grouse passed by and paid him no mind. He cooked on a Sibley stove and warded off loneliness with phone calls to the women at the Bridgewater radio station, one of whom was named Ethel Miller and later became his wife.

As nighttime closes in and the autumn air cools, not even a silhouette of the tree line remains visible along the darkening mountainside. Quietness trumps over the occasional sound of an evening bird or small creatures trampling on fallen brown leaves. The watchman retreats to his cabin and huddles around a Kerosene lamp, as occasional storms provide the only source of natural luminescence with lightning that could jolt a man's nerves straight through. This is the solitude of the vigilant life of a fire tower watchman like Gerald Fawley, who spent his days over 4,000 feet in the air on Shenandoah Mountain.

Gerald Fawley, Class of 1935, had just graduated from Broadway High School in Rockingham County when he landed a position with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). As a Local Enlisted Man (LEM), Fawley completed tasks from working as a typist to delivering lunches for work crews all over the Shenandoah Valley. After the CCC camp closed in 1937, Fawley had no trouble finding a new position. He began working with the Forest Service, a federal agency underneath the Department of Agriculture. Henceforth, Fawley’s work centered around the natural development and functional use of the newly renamed George Washington National Forest, known as Shenandoah National Forest from its founding in 1917 to 1932.

Lacking training or experience with explosives, the college-aged man hauled thousands of pounds of dynamite for the men he called "dynamite monkeys" who oversaw CCC road projects. When the fire season rolled around, the Forest Service posted Fawley at a steel lookout tower on the crest of Shenandoah Mountain at Bother Knob. From his metal perch, Fawley watched for potential forest fires and phoned a dispatch station in Bridgewater if smoke or flames arose. He found entertainment in the wildlife of his workplace— turkeys, rabbits, foxes, and grouse passed by and paid him no mind. He cooked on a Sibley stove and warded off loneliness with phone calls to the women at the Bridgewater radio station, one of whom was named Ethel Miller and later became his wife.

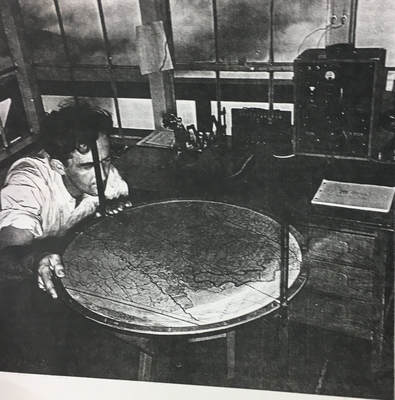

Gerald Fawley in the observation room of High Knob Tower using an Osborne fire finder. USFS photo.

Gerald Fawley in the observation room of High Knob Tower using an Osborne fire finder. USFS photo.

Fire Detection - How It Worked

During the fire tower era, the Forest Service fire program had three goals: prevent, detect and suppress wildfires. According to Terry Slater, former Dry River Fire Program Manager, fire watchmen were connected by telephone and worked together to detect fires. One would spot smoke and use the Osborne fire finder (pictured) to determine the direction. He would telephone a fire watch in another fire lookout using the lines that ran along the top of Shenandoah Mountain. Hiker can still find insulators in trees. The second lookout would then aim his fire finder at the smoke and, by triangulation, the fire's location could be determined and given to firefighters. Fire departments in communities in the Valley would then dispatch a crew to suppress the fire.

When Bother Knob went out of use due to its obstructed view of the surrounding mountains due to tree growth, the Forest Service transferred Fawley to the lookout post on High Knob five miles north of Bother Knob near Brandywine, WV. This former fireman’s lookout post lies within the proposed Shenandoah Mountain National Scenic Area and warrants protection due to its illustrious history, stunning views, and pertinence to local natural heritage.

During his first fire season at High Knob, Fawley roomed with Abner Casey, a district forest ranger who lived on nearby private property. The lookout man and the ranger’s family had breakfast together each morning before Fawley made the steep mile-long hike that led to the knoll with a panoramic view of Virginia and West Virginia. There, he would shimmy up a tree with wooden slats nailed in. He sat in a makeshift hunter's stand, but unlike the hunters of the forest, lookout men carried no weapons to their solitary mountain posts.

During the fire tower era, the Forest Service fire program had three goals: prevent, detect and suppress wildfires. According to Terry Slater, former Dry River Fire Program Manager, fire watchmen were connected by telephone and worked together to detect fires. One would spot smoke and use the Osborne fire finder (pictured) to determine the direction. He would telephone a fire watch in another fire lookout using the lines that ran along the top of Shenandoah Mountain. Hiker can still find insulators in trees. The second lookout would then aim his fire finder at the smoke and, by triangulation, the fire's location could be determined and given to firefighters. Fire departments in communities in the Valley would then dispatch a crew to suppress the fire.

When Bother Knob went out of use due to its obstructed view of the surrounding mountains due to tree growth, the Forest Service transferred Fawley to the lookout post on High Knob five miles north of Bother Knob near Brandywine, WV. This former fireman’s lookout post lies within the proposed Shenandoah Mountain National Scenic Area and warrants protection due to its illustrious history, stunning views, and pertinence to local natural heritage.

During his first fire season at High Knob, Fawley roomed with Abner Casey, a district forest ranger who lived on nearby private property. The lookout man and the ranger’s family had breakfast together each morning before Fawley made the steep mile-long hike that led to the knoll with a panoramic view of Virginia and West Virginia. There, he would shimmy up a tree with wooden slats nailed in. He sat in a makeshift hunter's stand, but unlike the hunters of the forest, lookout men carried no weapons to their solitary mountain posts.

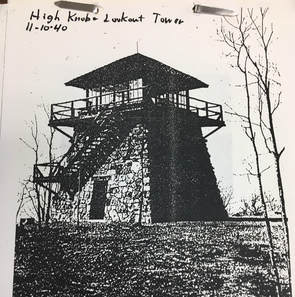

The newly constructed High Knob Fire Tower in 1940. USFS file.

The newly constructed High Knob Fire Tower in 1940. USFS file.

Construction of High Knob Fire Tower

In 1939, planning began for a lookout structure on High Knob. The construction project proved beneficial for postwar employment in the area. Veterans of World War I worked alongside crews from CCC Camp #2 at North River to build High Knob Fire Tower. They constructed it with native rock from the mountaintop, making it the only stone tower in our region. For maximum visibility, its design included a catwalk and an interior room with windows on each side. Working in the off-season prevented the building project from interfering with lookout duties, and by the 1940 fire season, Gerald Fawley no longer had to do his work from a rickety platform in the limbs of a tree. He instead made himself at home within the stone tower's interior, where he worked for three more seasons before transferring to the post on Cow Knob, which sits on the border of Rockingham County, VA and Pendleton County, WV.

End of the Fire Tower Era

In the late 1960s into the early 70s, the George Washington Forest Service considered the usefulness of fire towers and whether they should be taken down. Despite the illustrious history of the towers, a call came in the early 1970s to remove all the fire towers within the George Washington National Forest, including High Knob. On August 28th, 1972, Melvin L. Anhold, Fire Control Staff Officer, wrote to all District Rangers,

In 1939, planning began for a lookout structure on High Knob. The construction project proved beneficial for postwar employment in the area. Veterans of World War I worked alongside crews from CCC Camp #2 at North River to build High Knob Fire Tower. They constructed it with native rock from the mountaintop, making it the only stone tower in our region. For maximum visibility, its design included a catwalk and an interior room with windows on each side. Working in the off-season prevented the building project from interfering with lookout duties, and by the 1940 fire season, Gerald Fawley no longer had to do his work from a rickety platform in the limbs of a tree. He instead made himself at home within the stone tower's interior, where he worked for three more seasons before transferring to the post on Cow Knob, which sits on the border of Rockingham County, VA and Pendleton County, WV.

End of the Fire Tower Era

In the late 1960s into the early 70s, the George Washington Forest Service considered the usefulness of fire towers and whether they should be taken down. Despite the illustrious history of the towers, a call came in the early 1970s to remove all the fire towers within the George Washington National Forest, including High Knob. On August 28th, 1972, Melvin L. Anhold, Fire Control Staff Officer, wrote to all District Rangers,

"Our fire tower detection system is not effective. This came out by analyzing the fire reports. We are proposing to go to a full aerial detection system. Therefore, it will no longer be necessary to maintain or man fire towers. We propose that all fire towers be declared surplus and removed, with the exclusion of Elliott Knob and Reddish Knob.”

Scenic view to the north from High Knob Fire Tower. Photo by Caroline Whitlow

Scenic view to the north from High Knob Fire Tower. Photo by Caroline Whitlow

David Frankel, adjutant of the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States Post 632, wrote a letter on September 10th, 1969, to George Washington National Forest Supervisor Stanford M. Adams complaining about the lack of accessibility to High Knob Fire Tower. At the time, Frankel said that because the road to the tower was built partially on private land, there had been a locked gate barring access to anyone besides Forest Service members who maintained the tower and the private citizens who owned land along that road. Frankel and the rest of Post 632 requested that the Forest Service open the road to High Knob for public travel. The significance of the tower, to Frankel, came from the fact that the structure was “erected by World War I veterans, stationed at a CCC camp in Augusta County,” and had "potential to be a memorial to those men who served their country with honor.” Not only was Frankel writing to keep the tower open to the public, he also fought for the tower to stay erect, an issue to come up just a few years later.

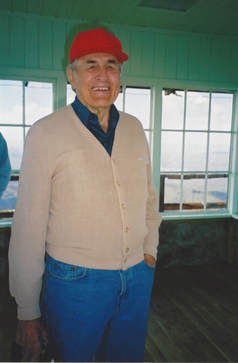

Gerald Fawley in the newly restored High Knob Fire Tower. Photo by Lynn Cameron

Gerald Fawley in the newly restored High Knob Fire Tower. Photo by Lynn Cameron

In Defense of High Knob Fire Tower

With improvements in technology, it seems natural to remove old methods; however, fire towers are much different. This difference lies in the fact that fire towers can go out of use for their original purpose, but they still offer a beautiful view and landmark for the public to enjoy for years to come and represent an important era in our national forests. Due to interest from the public, Frankel, and many Forest Service workers, submitted a justification for the exclusion of High Knob from destruction just a week after Anhold’s notice.

District Ranger Ray Mason wrote to Anhold on September 5th, 1972 requesting that the Forest Service retain High Knob tower. Mason explained that the fire tower “would make a good visitor lookout… and has excellent views.” He briefly mentioned the historical significance because of the veterans who helped build it. Mason goes on to say that the “local VFW and Rockingham Historical Society have expressed interest in its retention.” After Frankel's letter, the VFW had continuously submitted more in support of preserving the tower. Due to its acceptance as a public landmark, the fire tower required maintenance to ensure its safety and accessibility for visitors to enjoy.

Restoring the Tower

The decision to restore High Knob Fire Tower was not taken lightly. For restoration projects like this one, it is vital to maintain the original aesthetic while repairing and improving the structure. The 360-degree panoramic views from High Knob along with its stone structure set it apart from the steel towers of the area and make it especially alluring. A past forest archaeologist by the name of Lee Certain stated,

With improvements in technology, it seems natural to remove old methods; however, fire towers are much different. This difference lies in the fact that fire towers can go out of use for their original purpose, but they still offer a beautiful view and landmark for the public to enjoy for years to come and represent an important era in our national forests. Due to interest from the public, Frankel, and many Forest Service workers, submitted a justification for the exclusion of High Knob from destruction just a week after Anhold’s notice.

District Ranger Ray Mason wrote to Anhold on September 5th, 1972 requesting that the Forest Service retain High Knob tower. Mason explained that the fire tower “would make a good visitor lookout… and has excellent views.” He briefly mentioned the historical significance because of the veterans who helped build it. Mason goes on to say that the “local VFW and Rockingham Historical Society have expressed interest in its retention.” After Frankel's letter, the VFW had continuously submitted more in support of preserving the tower. Due to its acceptance as a public landmark, the fire tower required maintenance to ensure its safety and accessibility for visitors to enjoy.

Restoring the Tower

The decision to restore High Knob Fire Tower was not taken lightly. For restoration projects like this one, it is vital to maintain the original aesthetic while repairing and improving the structure. The 360-degree panoramic views from High Knob along with its stone structure set it apart from the steel towers of the area and make it especially alluring. A past forest archaeologist by the name of Lee Certain stated,

“This tower is unique because it is the only stone tower in the state and the only one intact on National Forest lands east of the Mississippi River.”

The newly restored High Knob Fire Tower in 2003. Photo by Lynn Cameron

The newly restored High Knob Fire Tower in 2003. Photo by Lynn Cameron

The uniqueness of the tower was a major contributor to it being put on the registry. Not only did Certain understand its importance, many others also did, like Bud Risner, former Dry River District Ranger, and Gerard Jacques, former forest fire and lands staff officer. These two men were responsible for nominating High Knob Tower for the National Historic Lookout Register.

According to Jacques, “[These towers] are a symbol of conservation,” so it is only natural to protect them. Despite not being used as a fire tower anymore, High Knob Tower is still a beautiful landmark that is open to the public with the help of the restoration project and continued maintenance by the Forest Service.

The project came into discussion in December 1996 with an excess of $50,000 in the state's superfund. Restoration of High Knob Fire Tower was just one of many ideas of how to use the money. The idea to restore the tower grew in popularity, and the excess in the superfund was allotted to this cause.

According to Jacques, “[These towers] are a symbol of conservation,” so it is only natural to protect them. Despite not being used as a fire tower anymore, High Knob Tower is still a beautiful landmark that is open to the public with the help of the restoration project and continued maintenance by the Forest Service.

The project came into discussion in December 1996 with an excess of $50,000 in the state's superfund. Restoration of High Knob Fire Tower was just one of many ideas of how to use the money. The idea to restore the tower grew in popularity, and the excess in the superfund was allotted to this cause.

Gerald Fawley, at 86 years old, hiked from Rt. 33 up to High Knob Fire Tower for the dedication of the renovation in 2003. He recounted memories of his days as a fire watch. Shown here with Terry Slater. Photo by Lynn Cameron

Gerald Fawley, at 86 years old, hiked from Rt. 33 up to High Knob Fire Tower for the dedication of the renovation in 2003. He recounted memories of his days as a fire watch. Shown here with Terry Slater. Photo by Lynn Cameron

The cost of restoring the tower was $39,500, and the cost to add parking and to clear out a trail for High Knob was an additional $100,000 for a total of $139,500. This project could not have been completed without the help of local community partners, including:

In the initial planning, the Dry River Ranger District project leaders, Terry Slater, District Fire Staff Officer, and Bob Tennyson, District Recreation Staff Officer, set out these project goals:

- State Historic Preservation Offices, VA & WV

- James Madison University fraternities and sororities

- West Virginia Department of Transportation

In the initial planning, the Dry River Ranger District project leaders, Terry Slater, District Fire Staff Officer, and Bob Tennyson, District Recreation Staff Officer, set out these project goals:

- To restore High Knob Fire Tower to its original condition, making it safe for public enjoyment, and, usable for fire detection on days of extreme fire danger, and

- To provide parking and access by way of a hiking trail of relatively easy difficulty to this historic landmark. The tower is currently unsafe for use by visitors; access is by way of a very difficult three-mile hike from Brandywine recreation area, an elevation difference of over 2000’.

Reddish Knob Fire Tower. Photo from GWNF files

Reddish Knob Fire Tower. Photo from GWNF files

What Ever Happened to Reddish Knob Tower?

Unfortunately, a common issue with historical sites, natural trails, and any other public land area is the susceptibility to vandalism. Specifically, there was a letter written by an unknown source that described Reddish Knob’s role in fire tower use and subsequent struggles with vandalism. This letter was in response to the abuse that caused its removal in 1975.

Dale Smith, a person who held Reddish Knob close to his heart, visited that fire tower throughout his entire life. When Dale was just a toddler, his father would bring him to the top of this tower, which conjures many fond memories of this landmark. To see it vandalized, for Dale, “[brought] out emotions of many years.” Because this crime felt so personal to a local who had grown up with the tower, Dale and his friends paid the government $400 to dismantle it themselves. They had planned to relocate the structure, but did not want to open it back up to the public because “They had their chance and they blew it.”

This story of the Reddish Knob Tower's dismantlement is not the only of its kind when it comes to fire towers. High Knob continuously undergoes vandalism from broken windows, smashed in doors, broken pieces of wood and hand rails, and so much more. The Forest Service does its best to continue fixing and replacing certain parts of the tower, but this constant repair may not remain tolerable for years to come.

Maintenance of the tower is an important part of local conservation efforts. With very few remaining fire towers in the Eastern United States, and even fewer made of stone, High Knob plays an important role in the narrative of firefighting history. It also showcases the construction efforts that provided employment to war veterans and those affected by the Great Depression during the early 20th century.

Unfortunately, a common issue with historical sites, natural trails, and any other public land area is the susceptibility to vandalism. Specifically, there was a letter written by an unknown source that described Reddish Knob’s role in fire tower use and subsequent struggles with vandalism. This letter was in response to the abuse that caused its removal in 1975.

Dale Smith, a person who held Reddish Knob close to his heart, visited that fire tower throughout his entire life. When Dale was just a toddler, his father would bring him to the top of this tower, which conjures many fond memories of this landmark. To see it vandalized, for Dale, “[brought] out emotions of many years.” Because this crime felt so personal to a local who had grown up with the tower, Dale and his friends paid the government $400 to dismantle it themselves. They had planned to relocate the structure, but did not want to open it back up to the public because “They had their chance and they blew it.”

This story of the Reddish Knob Tower's dismantlement is not the only of its kind when it comes to fire towers. High Knob continuously undergoes vandalism from broken windows, smashed in doors, broken pieces of wood and hand rails, and so much more. The Forest Service does its best to continue fixing and replacing certain parts of the tower, but this constant repair may not remain tolerable for years to come.

Maintenance of the tower is an important part of local conservation efforts. With very few remaining fire towers in the Eastern United States, and even fewer made of stone, High Knob plays an important role in the narrative of firefighting history. It also showcases the construction efforts that provided employment to war veterans and those affected by the Great Depression during the early 20th century.

Gerald Fawley and Carol Maureen DeHart, January 10, 2006. Courtesy of Carol DeHart.

Gerald Fawley and Carol Maureen DeHart, January 10, 2006. Courtesy of Carol DeHart.

Preserving the Stories

Carol Maureen DeHart, a former firefighter and Shenandoah Valley historian, has worked to preserve the past of these structures. "I started interviewing for James Madison University Libraries, and since I worked with the Forest Service, I often interviewed firefighters. I really wanted to find out about the towers," said DeHart. The interviews led her to Gerald Fawley, who was over 80 years old at the time, and his experience at High Knob. "I fell in love with that tower. I've seen a lot of them, and that one is just so beautiful in particular," said DeHart. While she never worked as a lookout in the East, DeHart manned a tower in Arizona, and she described the solitude of the structures as a special feeling. "It had a magnificent view. You could see the Grand Canyon. Then on some days, it felt like a terrarium. I couldn't see past the windows. It was a very haunting feeling, but it was never lonely," said DeHart. DeHart hopes that her work will encourage conservation efforts like the one that preserved High Knob after it went out of use.

Although new technology has eliminated the necessity to staff fire towers around Shenandoah Mountain, High Knob remains an important part of local culture and recreation. Hikers from near and far frequent the trail, which also provides access to a lake and campground at Brandywine. The tower's catwalk is accessible to visitors and offers a 360-degree view of both Virginia and West Virginia. National Geographic featured High Knob Fire Tower on the cover of "Staunton/Shenandoah Mountain Trails Illustrated Map 791."

Carol Maureen DeHart, a former firefighter and Shenandoah Valley historian, has worked to preserve the past of these structures. "I started interviewing for James Madison University Libraries, and since I worked with the Forest Service, I often interviewed firefighters. I really wanted to find out about the towers," said DeHart. The interviews led her to Gerald Fawley, who was over 80 years old at the time, and his experience at High Knob. "I fell in love with that tower. I've seen a lot of them, and that one is just so beautiful in particular," said DeHart. While she never worked as a lookout in the East, DeHart manned a tower in Arizona, and she described the solitude of the structures as a special feeling. "It had a magnificent view. You could see the Grand Canyon. Then on some days, it felt like a terrarium. I couldn't see past the windows. It was a very haunting feeling, but it was never lonely," said DeHart. DeHart hopes that her work will encourage conservation efforts like the one that preserved High Knob after it went out of use.

Although new technology has eliminated the necessity to staff fire towers around Shenandoah Mountain, High Knob remains an important part of local culture and recreation. Hikers from near and far frequent the trail, which also provides access to a lake and campground at Brandywine. The tower's catwalk is accessible to visitors and offers a 360-degree view of both Virginia and West Virginia. National Geographic featured High Knob Fire Tower on the cover of "Staunton/Shenandoah Mountain Trails Illustrated Map 791."

Bibliography

DeHart, Carol. "High Knob Fire Tower." Interview. Interviewed by Caroline Whitlow and Tyler Gingrich. November 13, 2017.

Fawley, Gerald E. "Oral History Interview with Gerald E. Fawley." Interview. Interviewed by Carol DeHart. Virginia Wildlands Firefighters Special Collection, Carrier Library. January 10, 2006.

"High Knob Hike." Virginia Wilderness Committee. 2013. Accessed November 21, 2017.

"High Knob & Hoover Ridge." Virginia Trail Guide. April 22, 2013. Accessed November 22, 2017.

Miscellaneous documents. USDA Forest Service, North River Ranger District Office. Harrisonburg, VA.

DeHart, Carol. "High Knob Fire Tower." Interview. Interviewed by Caroline Whitlow and Tyler Gingrich. November 13, 2017.

Fawley, Gerald E. "Oral History Interview with Gerald E. Fawley." Interview. Interviewed by Carol DeHart. Virginia Wildlands Firefighters Special Collection, Carrier Library. January 10, 2006.

"High Knob Hike." Virginia Wilderness Committee. 2013. Accessed November 21, 2017.

"High Knob & Hoover Ridge." Virginia Trail Guide. April 22, 2013. Accessed November 22, 2017.

Miscellaneous documents. USDA Forest Service, North River Ranger District Office. Harrisonburg, VA.

- GWNF letter to deconstruct towers

- High Knob Tower, historical summary

- Letter from VFW to GWNF

- List of views from tower

- Newspaper article on tower registration

- NHLR Certificate

- Renovation budget

- Request from GWNF to keep tower

- Superfund project ideas

- Vandalism, Reddish Knob and High Knob

| Full document: High Knob Fire Tower by Tyler Gingrich and Caroline Whitlow | |

| File Size: | 1821 kb |

| File Type: | |