Flood of 1949

Cloudburst on Shenandoah Mountain

Introduction | Cloudburst on Shenandoah Mountain | Stokesville is Gone! | The Cramer Family | The Michael and Emmett Families

Strothertown | The 4-H Campers and Girl Scouts | Harry Jopson's Story | After the Flood

Strothertown | The 4-H Campers and Girl Scouts | Harry Jopson's Story | After the Flood

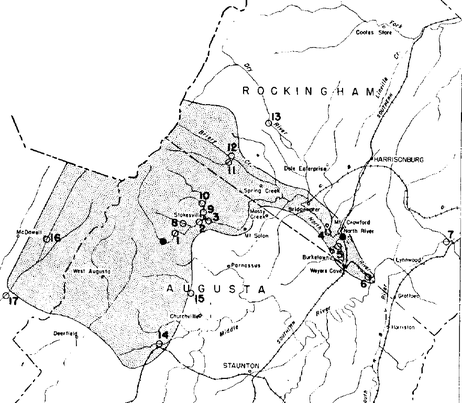

Area flooded on June 17-18, 1949. Map from USGS publication by Orville Mussey.

Area flooded on June 17-18, 1949. Map from USGS publication by Orville Mussey.

So what caused this 25-30-foot wall of water ("Forest Survey", 22 June 1949) to obliterate Stokesville and flood Bridgewater and other communities along the North River? The trouble started upstream on Shenandoah Mountain when a cloudburst dropped torrents of rain on already saturated ground in Little River, Hone Quarry, Briery Branch, and North River. The worst of these was Little River where the Forest Service estimated rainfall of 15 inches on June 17 on ground that was already saturated. ("Forest Survey" 22 June 1949)

The steep mountain slopes on Shenandoah Mountain had been deforested and burned repeatedly in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The newly formed Forest Service had acquired the land some 30 years prior to the flood and was managing it to restore the forest. When the large volume of rain hit, the mountainsides literally slid away, taking trees, stumps, rocks, mud and other debris. The Forest Service documented 75 landslides just in the Little River watershed. Most of these were on Buck Mountain and Timber Ridge, and many were visible from Reddish Knob Fire Tower. According to Richard Elliott, Dry River District Ranger, the water appears to have saturated the ground, worked under the soil and lifted it from its foundations. This action started numerous landslides that gathered momentum and cut a swath all the way from the mountaintop to the stream side in some cases. Some of the slides were smaller. Coupled with runoff from Little River and its tributaries, the cumulative effect was a wall of water. The deluge removed all vegetation from the Little River stream channel for a width of 200-300 feet and scoured the riverbed down to bedrock. After the flood Ranger Elliott described Little River as “a tiny stream in a mighty river bed.” ("Forest Survey" 15 July 1949)

It’s hard to believe, but Ranger Elliott said it could have been a lot worse:

The steep mountain slopes on Shenandoah Mountain had been deforested and burned repeatedly in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The newly formed Forest Service had acquired the land some 30 years prior to the flood and was managing it to restore the forest. When the large volume of rain hit, the mountainsides literally slid away, taking trees, stumps, rocks, mud and other debris. The Forest Service documented 75 landslides just in the Little River watershed. Most of these were on Buck Mountain and Timber Ridge, and many were visible from Reddish Knob Fire Tower. According to Richard Elliott, Dry River District Ranger, the water appears to have saturated the ground, worked under the soil and lifted it from its foundations. This action started numerous landslides that gathered momentum and cut a swath all the way from the mountaintop to the stream side in some cases. Some of the slides were smaller. Coupled with runoff from Little River and its tributaries, the cumulative effect was a wall of water. The deluge removed all vegetation from the Little River stream channel for a width of 200-300 feet and scoured the riverbed down to bedrock. After the flood Ranger Elliott described Little River as “a tiny stream in a mighty river bed.” ("Forest Survey" 15 July 1949)

It’s hard to believe, but Ranger Elliott said it could have been a lot worse:

Coal Run had the highest discharge, estimated at 1,840 cubic feet per second per square mile. (USGS, Orville Mussey, 1950) Photo of Coal Run watershed taken from Grooms Ridge Trail by Lynn Cameron

Coal Run had the highest discharge, estimated at 1,840 cubic feet per second per square mile. (USGS, Orville Mussey, 1950) Photo of Coal Run watershed taken from Grooms Ridge Trail by Lynn Cameron

The Flood

How much did it rain? That’s a hard question to answer. According to Orville D. Mussey, a hydraulic engineer and author of Flood of June 1949 in Stokesville-Bridgewater Area, this flood was “the result of torrential rains on a limited area” for which there are scant precipitation records available. This particular flood was a most unusual one, being the result of intense rainfall over a relatively small area in a mountainous, forested region confined largely to the headwaters of the North River. The drainages that had the highest discharge were: Little River, Coal Run, Skidmore Fork (where Todd Lake is now located), and North River. Of these, Coal Run had the highest estimated discharge with 1,840 cubic feet per second per square mile with Skidmore Fork in second place with 1,790. Mine Run, a tributary of Briery Branch only a few miles away, was only about 2 feet above low water, illustrating how localized the cloudburst was. (Mussey 1949)

National Weather Service records indicate a combination of high pressure over New England combined with a tropical low near Georgia set up a flow of moist tropical air from the Virginia Coast westward to the Alleghenies. As the air lifted over Shenandoah Mountain, flood-producing rains began. (National Weather Service 2016)

Historian John Wayland wrote:

How much did it rain? That’s a hard question to answer. According to Orville D. Mussey, a hydraulic engineer and author of Flood of June 1949 in Stokesville-Bridgewater Area, this flood was “the result of torrential rains on a limited area” for which there are scant precipitation records available. This particular flood was a most unusual one, being the result of intense rainfall over a relatively small area in a mountainous, forested region confined largely to the headwaters of the North River. The drainages that had the highest discharge were: Little River, Coal Run, Skidmore Fork (where Todd Lake is now located), and North River. Of these, Coal Run had the highest estimated discharge with 1,840 cubic feet per second per square mile with Skidmore Fork in second place with 1,790. Mine Run, a tributary of Briery Branch only a few miles away, was only about 2 feet above low water, illustrating how localized the cloudburst was. (Mussey 1949)

National Weather Service records indicate a combination of high pressure over New England combined with a tropical low near Georgia set up a flow of moist tropical air from the Virginia Coast westward to the Alleghenies. As the air lifted over Shenandoah Mountain, flood-producing rains began. (National Weather Service 2016)

Historian John Wayland wrote:

“The devastation in the Stokesville area and along the course of North River … is almost unbelievable. Nothing like it ever happened before within the period known by white people, and it is sincerely to be hoped that nothing like it will occur again. The place where the village of Stokesville was can hardly be located, and for miles farther down the stream debris is lodged against trees and bushes and wreckage is strewed widely over denuded fields and gardens. Bridges were washed away and great gullies are found at many places where hard-surfaced reads [sic] were before." (Wayland 13 August 1949)

Charles Noble, Assistant Ranger in the Dry River District of the George Washington National Forest, wrote that “a severe storm dropped approximately 15 inches of rain in less than 24 hours on ground already saturated. The center of this deluge was in the Little River – Briery Branch area.” (26 June 1962)

The mountainsides slid away

The rain saturated the mountainsides so fast that the water could not run off, causing over 75 landslides, most of which were on Buck Mountain and Timber Ridge. Some were quite visible from Reddish Knob, a popular viewpoint even back in 1949. The Forest Service documented the landslides and beginning in 1959, tried to stabilize and revegetate steep, bare slopes that were devoid of topsoil. These efforts went on for over a decade. (Noble 26 June 1962)

With the North River at record heights and the Little River receiving 15+ inches of rainfall on Friday, it’s easy to see how Stokesville was hit so hard. The Little River and North River join at Camp May Flather. The two combined are responsible for the extensive damage to the little community just downstream of North River Gap.

The mountainsides slid away

The rain saturated the mountainsides so fast that the water could not run off, causing over 75 landslides, most of which were on Buck Mountain and Timber Ridge. Some were quite visible from Reddish Knob, a popular viewpoint even back in 1949. The Forest Service documented the landslides and beginning in 1959, tried to stabilize and revegetate steep, bare slopes that were devoid of topsoil. These efforts went on for over a decade. (Noble 26 June 1962)

With the North River at record heights and the Little River receiving 15+ inches of rainfall on Friday, it’s easy to see how Stokesville was hit so hard. The Little River and North River join at Camp May Flather. The two combined are responsible for the extensive damage to the little community just downstream of North River Gap.

Big Ridge in center with Buck Mountain in the distance to the right. Many of the 75 landslides were within this viewshed. Photo from Grooms Ridge Trail by Lynn Cameron.

Big Ridge in center with Buck Mountain in the distance to the right. Many of the 75 landslides were within this viewshed. Photo from Grooms Ridge Trail by Lynn Cameron.

Reddish Knob

The road to Reddish Knob was washed out and impassable. “The Reddish Knob road, a favorite route for those who wish to motor to the top of the mountain and view the scenery in Virginia and West Virginia has been closed to travel.” One washout was 200 feet long. ("Forest Roads" 22 June 1949) The “Tilman Cabin Rd. from Briery Branch to Stokesville [now called Tilman Rd. or Forest Road 101] was badly washed out and could not be travelled. Some hunting cabins were washed downstream. ("North River Area" 12 June 1949) The Beam family was fortunate. Lee Beam said their cabin on Little River by Tilman Rd. “was built in the early 1930’s. The stories we heard from our father was that the river came into the yard, split and mostly went around the cabin (which lessened the force) but there was maybe 2’ of water in the cabin.” (Beam, 19 March 2018)

Needless to say, Norh River and Hone Quarry Recreation Areas were both closed for quite some time because of damage to the areas and to the roads leading to them. North River Recreation Area was hit the hardest. ("Forest Roads" 23 June 1949)

The road to Reddish Knob was washed out and impassable. “The Reddish Knob road, a favorite route for those who wish to motor to the top of the mountain and view the scenery in Virginia and West Virginia has been closed to travel.” One washout was 200 feet long. ("Forest Roads" 22 June 1949) The “Tilman Cabin Rd. from Briery Branch to Stokesville [now called Tilman Rd. or Forest Road 101] was badly washed out and could not be travelled. Some hunting cabins were washed downstream. ("North River Area" 12 June 1949) The Beam family was fortunate. Lee Beam said their cabin on Little River by Tilman Rd. “was built in the early 1930’s. The stories we heard from our father was that the river came into the yard, split and mostly went around the cabin (which lessened the force) but there was maybe 2’ of water in the cabin.” (Beam, 19 March 2018)

Needless to say, Norh River and Hone Quarry Recreation Areas were both closed for quite some time because of damage to the areas and to the roads leading to them. North River Recreation Area was hit the hardest. ("Forest Roads" 23 June 1949)

Staunton Dam was the only dam on Shenandoah Mountain when the Flood of 1949 occurred. The gauge at the dam showed a peak level of 10.9 feet and a discharge of 11,100 cubic feet per second. Photo by Lynn Cameron

Staunton Dam was the only dam on Shenandoah Mountain when the Flood of 1949 occurred. The gauge at the dam showed a peak level of 10.9 feet and a discharge of 11,100 cubic feet per second. Photo by Lynn Cameron

Staunton Dam

Staunton Dam was the only dam that had been built on the North River and its tributaries when the 1949 flood occurred. The concrete dam and tunnel through Hankey Mountain had been built in the 1920s to provide municipal water for Staunton. During the flood, there were rumors the dam had breached, but in fact, it held, even with record levels of flow. The gauge at the dam showed a peak level of 10.9 feet and a discharge of 11,100 cubic feet per second at around 10 p.m. Friday night. (Mussey 1949). It's a good thing the dam held as there were 80 Augusta County 4-H Club members and leaders camped at North River Recreation Area. Fortunately, no one was lost or injured in the flood.

Staunton Dam was the only dam that had been built on the North River and its tributaries when the 1949 flood occurred. The concrete dam and tunnel through Hankey Mountain had been built in the 1920s to provide municipal water for Staunton. During the flood, there were rumors the dam had breached, but in fact, it held, even with record levels of flow. The gauge at the dam showed a peak level of 10.9 feet and a discharge of 11,100 cubic feet per second at around 10 p.m. Friday night. (Mussey 1949). It's a good thing the dam held as there were 80 Augusta County 4-H Club members and leaders camped at North River Recreation Area. Fortunately, no one was lost or injured in the flood.

References

Beam, Lee. Email correspondence. 19 March 2018.

"Forest Areas Are Closed," Daily News Record, 23 June 1949.

"Forest Roads Flood Damage Said $150,000," Staunton News Leader, 22 June 1949.

“Forest Survey Shows What Created Flood in North River Area,” Daily News Record, 15 July 1949.

Mussey, Orville D. Flood of June 1949 in the Stokesville-Bridgewater Area. Charlottesville: Virginia Department of Conservation and Development in cooperation with the U.S. Geological Survey. 1950.

National Weather Service. "Flood event of 6/17/1949-6/20/1949." https://www.weather.gov/media/marfc/Flood_Events_2016/1949/Jun17-20%2C1949.pdf.

Noble, Charles. Memo on Restoration (Little River Slide Revegetation - Plans), 26 June 1962. Courtesy of George Washington National Forest North River Ranger District.

"North River Area Forest Roads Badly Damaged," Daily News-Record, 21 June 1949.

Wayland, John. Notes from 13 August 1949. Courtesy of Bridgewater College Library Special Collection.

Further Reading:

Hack, J. T. and Goodlett, J. C. Geomorphology and forest ecology of a mountain region in the central Appalachians.

USGS Professional Paper 347, 1960. This is about the Flood of 1949 in the Little River area.

Osterkamp, W. R., Hupp, C. R. and.Schening, M. R. "Little River revisited — thirty-five years after Hack and Goodlett" in Biogeomorphology, Terrestrial and Freshwater Systems. Elsevier, 1995. pp. 1-20.

Beam, Lee. Email correspondence. 19 March 2018.

"Forest Areas Are Closed," Daily News Record, 23 June 1949.

"Forest Roads Flood Damage Said $150,000," Staunton News Leader, 22 June 1949.

“Forest Survey Shows What Created Flood in North River Area,” Daily News Record, 15 July 1949.

Mussey, Orville D. Flood of June 1949 in the Stokesville-Bridgewater Area. Charlottesville: Virginia Department of Conservation and Development in cooperation with the U.S. Geological Survey. 1950.

National Weather Service. "Flood event of 6/17/1949-6/20/1949." https://www.weather.gov/media/marfc/Flood_Events_2016/1949/Jun17-20%2C1949.pdf.

Noble, Charles. Memo on Restoration (Little River Slide Revegetation - Plans), 26 June 1962. Courtesy of George Washington National Forest North River Ranger District.

"North River Area Forest Roads Badly Damaged," Daily News-Record, 21 June 1949.

Wayland, John. Notes from 13 August 1949. Courtesy of Bridgewater College Library Special Collection.

Further Reading:

Hack, J. T. and Goodlett, J. C. Geomorphology and forest ecology of a mountain region in the central Appalachians.

USGS Professional Paper 347, 1960. This is about the Flood of 1949 in the Little River area.

Osterkamp, W. R., Hupp, C. R. and.Schening, M. R. "Little River revisited — thirty-five years after Hack and Goodlett" in Biogeomorphology, Terrestrial and Freshwater Systems. Elsevier, 1995. pp. 1-20.